Auckland Rail Maps

Git repository: Link

14/10/2024

Overview

Auckland, New Zealand has notoriously terrible transport. It was bad enough in 2017 that it was estimated to be costing the city almost $2 billion per year in lost productivity and this number has no doubt become worse since then. You could build a lot of useful infrastructure with that sort of money.

While a heavy rail loop underneath the CBD is under construction it is questionable whether this will add enough capacity to ease the problem. Aside from that the New Zealand government has inexplicably been mostly interested in applying light rail to the issue, both as part of a second harbour crossing and an Auckland airport connection. These strangely circuitous projects have since been cancelled, and as they were only light rail and generally still included a focus on more direct car routes they were unlikely to have been effective at reducing congestion anyway. Overall, the situation remains dire.

But let's suppose there is a sudden outbreak of common sense, priorities are reworked to be more sane, and enough political will becomes available to make Auckland's rail network functional. What could that look like?

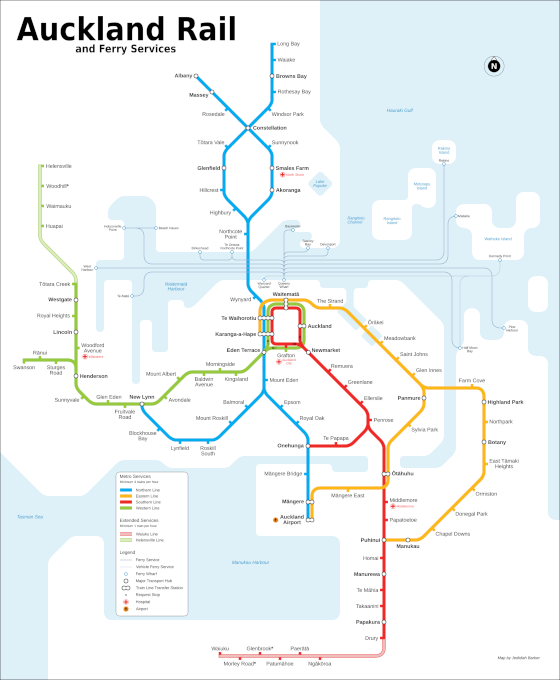

The above map was constructed as a 2240x2720 SVG and has been exported as a PNG here. Click to open a full scale version. Similar styling was used to the current Auckland rapid transit network map, and since that map has ferries as well, why not have them here too?

Line Differences and Notes

While there are really only four rail lines on this map, each of them branches once it leaves the centre of the city. This strikes a reasonable balance between service frequency and coverage vs population density. In addition, two extended services out to Helensville and Waiuku occupy a nebulous area that goes outside of the Auckland urban boundary but doesn't really qualify as intercity. Nevertheless, those rail corridors are already there so using them to provide effective transport makes sense.

Metro lines:

- Northern: This is the main addition. The corridor from Akoranga to Rosedale covers what is currently the Northern Busway. Running alongside a motorway is not ideal for a metro line, but we will come back to that. The branches from the new Mount Eden station to New Lynn and Auckland Airport approximately cover the same area the light rail airport proposal would have covered except much more direct and hence likely to be used. Finally, the section up through Browns Bay is a matter of ensuring decent coverage and allowing for a connection to Whangaparāoa and beyond.

- Eastern: Rail from Ōtāhuhu to the airport replaces the current AirportLink bus. The branch through Botany to join up to the existing stub at Manukau covers a lot of the same area the Southwest Gateway bus rapid transit would cover. A missing station at Saint Johns is added. The Strand becomes a regular metro station connected in with the rest of the network.

- Southern: Not a whole lot of change here. The Onehunga line is now just a branch of this line, trains now go around the loop formed by the City Rail Link, and the line extends to Drury.

- Western: Also not a whole lot of change here. Trains also go around the loop formed by the City Rail Link, and a new branch is added out to Westgate. Trains on this line no longer go to Newmarket.

Extended services:

- Waiuku: Makes use of the old Waiuku branch railway and incorporates the new stations at Ngākōroa and Paerātā. Notably this does not involve trains to Pukekohe at all, as those are left for intercity services.

- Helensville: Makes use of the old alignment heading north. Trains actually going towards Whangārei would use a brand new alignment via Hibiscus Coast, but this section remains useful for freight and the few small settlements that exist. Woodhill station is to allow for people to travel to and from the mountain bike park there without needing a car.

Two stations have been conspicuously renamed. Parnell station is now Auckland station because that is the only suitable location with enough space for a proper intercity rail terminus that connects reasonably well with the rest of the network. Maungawhau station is now Eden Terrace because the recent renaming from Mount Eden to a Maori word for mountain and trees was pointless since the meaning is the same. Further, doing so while claiming it to be from drawing on intergenerational wisdom shows it to be obvious political nonsense. The station itself ends up being barely in bounds of the suburb of Eden Terrace after being restructured from the City Rail Link, so it gets the suburb name. The new Mount Eden station on the map is further south down near the Mount Eden shops.

A new ferry line to Te Atatū Peninsula has been added. This would require around a kilometre of dredging, but otherwise stands out as the only potential expansion for ferry services with minimal impact to the harbour.

Unmapped Features

Each line has its own dedicated track. This generally means a track pair, except in the city centre where the Western and Southern lines each operate in a one way loop and so use a single track each. In total this means Te Waihorotiu and Karanga-a-Hape stations end up with six tracks each, with Waitematā having four.

Having dedicated track isn't just for isolating each line into its own sector to improve service reliability. It's outright necessary for capacity. On the map it is noted that each line gets a minimum of 4 trains per hour. That's on each branch, so towards the centre of the system that becomes 8 trains per hour. But during peak times it's expected for those numbers to double. At the busiest stations mentioned above that ends up being 48 trains per hour which a fair bit more than could fit if lines were sharing.

Yes, this does mean the City Rail Link project is woefully lacking for the task.

The extended services out to Waiuku run express between Papakura and Newmarket. Similarly, the extended services to Helensville run express between Henderson and Eden Terrace.

Actual intercity services have been left off the map completely. Figuring those out will be an entirely separate project. Likely included out of Auckland would be train services south to Hamilton, Tauranga, and Rotorua, train services north to Hibiscus Coast and Whangārei, ferry services to Gulf Harbour, Tryphena, and Coromandel, and a long distance train to Wellington. The train services would all operate from Auckland station and share track with the metro lines. Auckland station itself would have an extra six terminating platforms to accommodate this.

Passing loops would be needed for maintaining high capacity while running the extended services and intercity trains express on their way into and out of the city as well as allowing for freight. Eventually quadruplicating track on significant portions of the Western, Northern, and Southern lines will become necessary.

The proposed Avondale-Southdown line makes no appearance because, while useful and necessary, it is a freight rail connection.

Points of Contention and Comparison

Let us address a few questions and objections that may come up.

Is the capacity of heavy rail really needed?

Comparing the passenger capacity of different modes of mass transport to decide what will work is often a messy subject. As bus rapid transit systems have proven, it is possible to add dedicated right-of-ways, fare payments before boarding, more doors per vehicle, more platforms per station, and other optimisations to just about anything. Those things will never apply much to something that has to contend with mixed traffic on public roads, but let us assume they do. What difference is left? Only the number of passengers per vehicle.

| Bus | Bendy Bus | Light Rail | Heavy Rail (6 car) |

Heavy Rail (9 car) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Capacity |

90 | 150 | 340 | 750 | 1125 |

Figures are approximate and assume an articulated bus of 18m length, a tram of 45m length similar to an Alstom Citadis 405, and trains similar to a New Zealand AM class, all operating at maximum nominal seating and standing capacity. All other things being equal, building light rail lines to replace buses would get a 2-4x increase. Even if this successfully addressed the traffic problems in Auckland today it would leave little to no headroom for future growth as higher density housing is built to solve New Zealand's housing shortage. Transport infrastructure has to last decades. This detail has already caught the City Rail Link out requiring some reworking before completion. The capacity from heavy rail is really the only sensible option for future proofing. Note also that the heavy rail numbers given here are somewhat lower than what they could be due to the need to operate on the steep alignment of said City Rail Link.

What about the cost?

The projected cost of the 2023 second harbour crossing proposal was $35-45 billion NZD. This was outrageous on several levels, such as how the plan involved adding further inefficient car capacity which would have been pure waste. But most importantly, that price tag. Fortunately such ridiculous prices are not inevitable.

There are tricks to keeping the costs of building a subway or other metro system down, as multiple people have written at length about. Doing some back of the envelope calculations with numbers from the Transit Costs Project adjusted for inflation and with further margin added, it is likely that if New Zealand were to do things similarly to how things are done in places like Madrid, Spain, then everything on the map proposed here could become a reality for less money than that 2023 amount. Good value, that. Especially if viewed on a per passenger capacity basis.

Is a rail system this big really called for in a city like Auckland?

The city of Copenhagen in Denmark is surprisingly similar to Auckland in terms of size and population. They both have around 1.4-1.5 million residents in their urban areas and they both have an average urban density of around 2400-2500 people per square kilometre.

Both cities are located on islands called (New) Zealand too. That one is definitely a coincidence however, since the etymology is unrelated.

The useful point of comparison here is that Copenhagen has extensive passenger heavy rail in the form of their S-train system which has 170km of track. They also have light rail rapid transit in the form of the mostly underground Copenhagen Metro with 43km of track. And regular surface light rail under construction. It's all quite extensive. Meanwhile, Auckland currently only has around 105km of heavy rail. An approximate doubling of passenger rail system length in Auckland is thus entirely in line with what is known to be necessary in a city of comparable size. Especially when the high amount of bicycle usage in Copenhagen is taken into account, something Auckland does not have to ease traffic pressure.

Will all of this actually fix the traffic congestion issues?

Now that is an interesting question. The truth of the matter is most people use whatever mode of transport is convenient and that they are in the habit of using. If a city is designed to make high capacity modes convenient then everything works well. If a city is designed to make low capacity modes convenient then you get massive traffic problems.

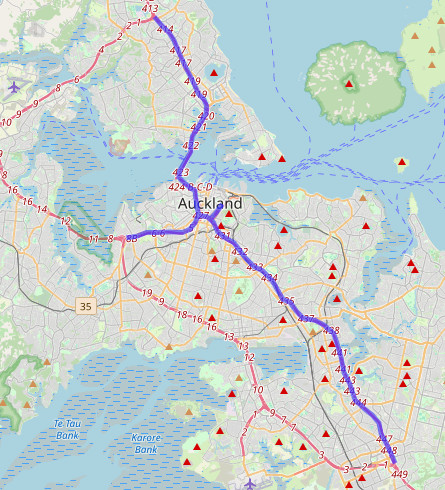

To go back to the Copenhagen comparison again, if you look at that city on a map you may notice something. There are no motorways that will take you into the city centre. Now I'm sure that is partially down to historical reasons, but that's not important. In Copenhagen it is easy to take heavy rail into the city and not so easy to drive. In Auckland it's currently the other way around. Building out passenger heavy rail to have a functional network would help a great deal, but it doesn't completely solve the problem. Those motorways leading right into the centre need to go.

The corridors are still important to have, since proper roads for traffic that isn't constantly stopping, starting, and turning unpredictably all the time is important from a safety and practicality point of view. But at the moment those corridors are set up primarily to dump up to 7600 vehicles per hour into the middle of the city. All that traffic comes from somewhere, and this is where. It's not even justified from a capacity viewpoint since nearly all cars at peak times only have one occupant and four lanes of such bumper to bumper traffic is less than seven of those max capacity 9-car trains mentioned earlier. Once the rail system is working properly, change these eight lane wide motorways to four lane regular roads and the traffic will disappear while people can still get to where they want to go.

Some of the space freed up by this redevelopment can be used for quadruplicating rail track where applicable. A lot of it can be used to add fully separated arterial cycleways. In particular, the harbour bridge can be reallocated to have four lanes for general car traffic, two lanes for buses and trucks, one lane for mopeds and microcars, and one lane for bicycles and pedestrians. Ironically all of this would actually increase its capacity. That is good though, since making it possible for more people to be able to get around Auckland easier is the whole goal here anyway.

Closing Remarks

For quite a while I had no idea where to even begin with Auckland's rail system. It's just that bad after decades upon decades of neglect. Then I saw the loop formed by the City Rail Link and things just started falling into place. I could go even further, connecting up Puhinui to Auckland Airport and reworking the map layout around New Lynn a bit, but I figured this was a good place to stop. For now.

Overall though, after a deep dive into all of this I strongly suspect the New Zealand government isn't really trying to solve this transport problem. No, I'm not talking about any sort of conspiracy. That would actually be easier to deal with. There are just too many ongoing institutional and ideological blindspots that prevent things being properly addressed. Most politicians still buy into the swindle of thinking that adding more cars, the lowest capacity mode of transport available, will somehow lead to anything but more traffic problems. Just as the most obvious example.

Too bad for the people who have to live in that city, I guess.